Elephants possess unique spinal structures adapted to distribute their immense body weight effectively, but these adaptations render them vulnerable to injury when used for riding in the tourism industry.

Elephant Spinal Health and Tourism

Pressure Points and Spinal Injuries

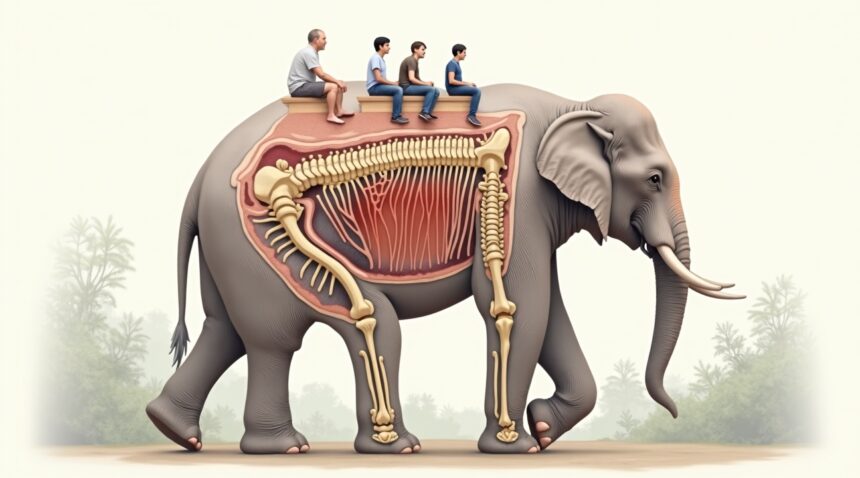

Unlike horses or traditional pack animals, elephants have convex, upward-arching spines that are anatomically unsuited for bearing external loads such as saddle equipment and human riders. This spinal configuration causes pressure to concentrate at specific points, leading to cumulative damage over time. These micro-injuries often go unnoticed until they result in severe health complications including spinal lesions, nerve damage, and persistent lameness.

Stoicism Masks Pain

Elephants are naturally stoic animals, making it difficult for tourists and handlers to recognize suffering. This trait hides chronic pain and discomfort, allowing serious structural damage to develop unnoticed under continued exploitation.

Conflicting Studies on Load-Bearing

Scientific data provides mixed conclusions—while some studies in controlled environments suggest elephants may carry up to 15–25% of their body weight for short periods, these findings often ignore the real-world context of tourism. Prolonged riding sessions, inadequate saddles, and poor handling in these settings rarely mirror laboratory conditions.

Saddles Amplify Harm

The saddles used in tourist rides typically rest on the elephant’s spine, creating intense stress on few areas rather than distributing the load evenly. This focal pressure can alter the animal’s natural gait, causing musculoskeletal disorders and long-term changes in movement patterns.

Ethical Tourism Alternatives

Fortunately, there is a growing shift within the tourism sector toward more compassionate alternatives. Ethical options include:

- Elephant sanctuaries that focus on rehabilitation and care instead of exploitation

- Observation-only eco tours promoting natural behaviors in the wild

- Educational experiences that raise awareness about elephant biology and conservation

Organizations and sanctuaries like Elephant Nature Park in Thailand are leading the way by offering immersive, non-invasive ways to connect with these majestic animals.

Why Elephant Spines Are Built for Their Own Weight, Not Tourist Riders

As the world’s largest land mammals, elephants carry an impressive natural burden. Adults typically weigh between 6,000 and 13,000 kg, and their massive skeletal structure has evolved specifically to support this extraordinary mass. However, I’ve learned through studying elephant anatomy that their spine design creates significant challenges when humans add external loads through tourism activities.

The elephant’s vertebral column differs dramatically from animals traditionally used for riding. While horses possess relatively flat backs suitable for saddles, elephants display a distinctly convex spine that arches upward. This curved structure works perfectly for distributing the animal’s own weight but creates concentrated pressure points when saddles or riding platforms are added. The pronounced bony protrusions called spinous processes further complicate matters, as they become vulnerable contact points where equipment can cause injury.

Natural Weight Distribution vs. Added Burdens

Elephants naturally distribute their massive weight through a carefully evolved system. Their forelimbs bear approximately 60% of their body weight, while the hind limbs support the remaining 40%. This distribution system works flawlessly for their own anatomy but wasn’t designed to accommodate additional concentrated loads positioned directly along the spine.

The absence of protective cushioning compounds these problems. Unlike some animals that have developed natural shock-absorbing fat pads over their spines, elephants lack this protective layer. Instead, thick interconnected connective tissues cover the vertebral area, which actually increases vulnerability to pressure-based injuries rather than providing protection.

When tourists climb aboard riding platforms or saddles, the concentrated weight creates localized stress points that the elephant’s spine simply cannot handle effectively. These pressure points can cause micro-injuries that accumulate over time, leading to chronic pain conditions that often go undetected by casual observers. Just as dangerous situations can develop in wildlife interactions, the structural mismatch between elephant anatomy and riding equipment creates serious welfare concerns that many tourism operations overlook in their daily activities.

The Hidden Suffering: How Elephants Mask Chronic Pain from Tourist Activities

Elephants possess an extraordinary ability to conceal physical discomfort, making their suffering from tourist activities largely invisible to the untrained eye. This remarkable stoicism stems from their survival instincts developed in the wild, where showing weakness could signal vulnerability to predators or rival elephants. Unfortunately, this natural behavior creates a dangerous situation where serious injuries accumulate silently beneath the surface.

Captive elephants frequently develop extensive physical injuries that go unnoticed by tourists and even some handlers. These injuries manifest as calluses, open wounds, spinal deformities, nerve damage, and chronic back pain. The anatomical structure of elephant spines makes them particularly vulnerable to damage from carrying loads, yet their instinctive response is to endure rather than display distress. This creates a cycle where injuries worsen over time without proper intervention.

Physical Evidence of Silent Suffering

The most concerning aspect of elephant tourism involves the damage that occurs beneath the visible surface. Documented cases reveal spinal lesions, pressure necrosis, and persistent lameness in elephants used for riding activities. Soft tissue damage affects skin, nerves, and ligaments in ways that aren’t immediately apparent to observers. These injuries develop gradually, creating chronic conditions that significantly impact the animal’s quality of life.

Spinal deformities represent one of the most serious consequences of improper load-bearing activities. The elephant’s spine wasn’t designed to support concentrated weight on their backs, leading to compression injuries and nerve damage. These conditions cause persistent pain that elephants endure silently, continuing to perform despite their discomfort. Similar to how some dangerous wildlife can hide their intentions, elephants masterfully conceal their pain from human observers.

Behavioral changes often provide the only visible clues to an elephant’s suffering:

- Reduced movement becomes apparent when elephants limit their natural range of motion to avoid triggering pain responses.

- Leg-shifting behavior indicates attempts to redistribute weight and relieve pressure on injured areas.

- Stereotypic swaying, characterized by repetitive side-to-side movements, serves as a coping mechanism for chronic discomfort.

Reluctance to comply with work demands represents another significant indicator of underlying pain. Elephants that previously participated willingly in tourist activities may begin showing resistance or hesitation. This behavioral shift often gets misinterpreted as stubbornness rather than recognized as a pain response. Handlers sometimes increase pressure or use corrective measures, further exacerbating the animal’s distress.

The challenge lies in recognizing these subtle signs before permanent damage occurs. Unlike more obvious injuries that would prompt immediate veterinary attention, the gradual onset of spinal problems and soft tissue damage requires careful observation and understanding of normal elephant behavior. Many facilities lack the expertise or resources to conduct thorough pain assessments, allowing conditions to progress unchecked.

This hidden suffering extends beyond individual animals to impact entire populations of captive elephants. The tourism industry’s demand for rideable elephants creates pressure to keep animals working despite developing health issues. Economic considerations often outweigh welfare concerns, particularly in regions where elephant tourism provides significant income for local communities.

Understanding this silent suffering requires recognizing that elephants’ stoic nature works against their best interests in captive situations. Their ability to endure pain without complaint, while admirable from a survival perspective, enables the continuation of harmful practices. Just as technological advances help us understand complex issues like space travel innovations, modern veterinary techniques and behavioral assessment tools provide better methods for detecting pain in elephants.

The responsibility falls on tourists, facility operators, and regulatory bodies to recognize these hidden signs of distress and advocate for more humane alternatives to traditional elephant tourism activities.

What Science Says About Elephants Carrying Weight

Scientific research provides mixed signals about elephants’ capacity to carry weight, creating a complex picture for wildlife tourism operators and conservationists. Peer-reviewed studies demonstrate that domesticated elephants can carry up to 15% of their body weight—roughly equivalent to two adult humans—without showing immediate changes to joint angles or gait during flat-terrain walking in short-term scenarios.

Laboratory Findings vs. Real-World Conditions

Some research pushes these limits further, suggesting elephants might safely carry up to 25% of their weight under controlled conditions. These laboratory-style studies, however, operate under ideal circumstances that rarely mirror the reality of elephant tourism operations. I’ve observed how research facilities maintain strict protocols that commercial operations often can’t replicate.

Laboratory studies typically exclude several critical factors that plague real-world elephant rides:

- Poor saddle design creates uneven weight distribution, leading to pressure points that concentrate stress on specific vertebrae.

- Continuous repetition throughout tourism seasons amplifies any negative effects.

- Extended duration rides push elephants beyond the brief testing periods used in most studies.

- Substandard husbandry practices, including inadequate rest periods and poor nutrition, compound stressors in ways that controlled research environments simply don’t capture.

The Chronic Pain Dilemma

The absence of immediate musculoskeletal damage doesn’t guarantee long-term welfare, and this distinction proves crucial for understanding elephant tourism’s true impact. Current research shows no conclusive evidence that occasional short rides result in immediate physical harm, yet this finding addresses only the tip of the iceberg regarding elephant welfare concerns.

Chronic pain represents the most significant gap in current scientific understanding. Elephants possess complex pain receptors and nervous systems, much like other large animals, yet researchers struggle to assess cumulative discomfort over extended periods. Traditional pain assessment methods designed for humans or smaller animals often fail to capture the subtle signs of chronic discomfort in elephants.

The vertebral structure that makes elephants ill-suited for carrying loads becomes particularly problematic over time. Unlike horses or camels, which evolved with naturally curved spines that distribute weight efficiently, elephants’ straight spinal columns transfer rider weight directly onto individual vertebrae. This anatomical reality suggests that even “safe” weight limits might cause cumulative damage when applied repeatedly over months or years.

Multi-year physical consequences remain largely unstudied, creating a critical knowledge gap in elephant welfare science. Most existing research focuses on immediate biomechanical responses rather than longitudinal health outcomes. Advanced imaging technologies could potentially reveal spinal degeneration or soft tissue damage that develops gradually, but such comprehensive studies require significant funding and time commitments.

Tourism operators often cite short-term research to justify their practices, yet these studies weren’t designed to assess the welfare implications of commercial elephant riding. The controlled conditions of research facilities—with their optimal nutrition, veterinary care, and limited work schedules—bear little resemblance to the conditions many tourism elephants experience.

The scientific community increasingly recognizes that absence of evidence isn’t evidence of absence when it comes to elephant welfare. Recent calls for stronger welfare guidelines reflect growing concern about the limitations of current research. Some researchers advocate for precautionary approaches that prioritize elephant welfare over tourism revenue, particularly given the irreversible nature of potential spinal damage.

Welfare assessment tools continue evolving, with researchers developing more sophisticated methods to detect stress hormones, behavioral changes, and physiological markers of discomfort. These advances may eventually provide clearer answers about the long-term consequences of carrying tourists, but current scientific knowledge remains incomplete regarding the full spectrum of welfare implications for elephants in tourism operations.

How Tourist Saddles Create Dangerous Pressure Points on Elephant Backs

Tourist activities place saddles and passengers directly onto elephant backs, creating concentrated pressure points that generate uneven and excessive spinal stress. I’ve observed how this artificial weight distribution differs dramatically from how elephants naturally carry their own body mass. The saddles focus weight on narrow regions of the spine rather than allowing for the natural distribution that occurs during normal elephant movement.

Understanding the Pressure Distribution Problem

Repetitive exposure to saddle-based strain amplifies microtraumas throughout the elephant’s back structure. These small injuries accumulate over time, creating conditions that wildlife veterinarians rarely encounter in wild elephant populations. The concentrated pressure points create several specific problems:

- Unnatural focal stress on vertebrae that weren’t designed to support external loads

- Compression of soft tissues between the saddle and bony spinal processes

- Disruption of natural muscle activation patterns during movement

- Creation of hot spots where blood flow becomes restricted under sustained pressure

Long-term exposure to these artificial stress patterns results in serious musculoskeletal disorders that compromise elephant welfare. Nerve pain develops as compressed tissues begin to deteriorate, while the constant adaptation to unnatural loading patterns causes alterations in the elephant’s natural gait and movement mechanics. These changes become permanent over time, much like how structural damage from earthquakes can permanently alter building foundations.

Unlike natural elephant behaviors such as walking, foraging, or dust bathing, riding activities introduce completely unnatural focal stress points that the elephant’s anatomy simply cannot accommodate safely. Wild elephants distribute their considerable body weight through four legs and sophisticated muscular systems that have evolved over millions of years. However, when tourists mount these animals, the additional concentrated load creates pressure patterns that exceed the spine’s natural capacity to adapt and recover.

The saddle itself becomes a rigid interface that cannot flex or adjust like the elephant’s own tissues would during natural movement. This inflexibility means that every step, turn, or change in terrain transmits jarring forces directly into the spinal column. The elephant’s natural shock-absorption systems become overwhelmed, leading to chronic inflammation and progressive joint deterioration.

Professional elephant care specialists have documented how these pressure-related injuries manifest differently from trauma patterns seen in wild populations. Captive elephants used for riding develop specific wear patterns on their vertebrae, compressed intervertebral spaces, and muscle atrophy in areas where saddles consistently rest. The animals often compensate by shifting their weight distribution, which creates secondary problems in their legs and feet.

Research into elephant biomechanics shows that even relatively light loads can create significant problems when concentrated through saddle contact points. The elephant’s spine, while incredibly strong for supporting the animal’s own distributed weight, becomes vulnerable when external forces focus on specific vertebrae. These concentrated loads exceed the tissue’s ability to repair itself between riding sessions.

The cumulative effect of repeated saddle use creates a cascade of physical problems that extend far beyond simple back pain. Elephants begin to modify their natural walking patterns to minimize discomfort, which places abnormal stress on joints throughout their bodies. This compensation mechanism eventually leads to arthritis, muscle imbalances, and reduced mobility that significantly impacts the animal’s quality of life.

Understanding these pressure dynamics helps explain why many elephant tourism operations have begun transitioning to observation-only experiences. The anatomical realities make it clear that saddle-based riding creates unavoidable welfare concerns that cannot be adequately addressed through improved equipment or reduced session times. The fundamental mismatch between elephant spinal anatomy and the demands of carrying external loads makes tourist riding an inherently problematic activity, regardless of how carefully it might be managed.

The Tourism Industry’s Shift Away from Elephant Riding

International animal welfare groups have spearheaded a rapidly growing movement against tourist elephant riding practices. These organizations recognize the severe anatomical limitations that make elephants unsuitable for carrying human passengers. Conservation groups and ethical tourism advocates work tirelessly to educate both operators and travelers about the hidden suffering these magnificent creatures endure.

Alternative Tourism Experiences Gaining Ground

Observation-only tourism has emerged as a compelling alternative to traditional riding experiences. Visitors can now witness elephants in their natural behaviors without causing physical harm to these gentle giants. Enrichment-based sanctuary programs allow tourists to observe feeding times, mud baths, and social interactions that showcase authentic elephant behavior.

Many tourism operations have recognized the ethical concerns and voluntarily reduced or eliminated elephant riding from their offerings. These forward-thinking businesses pursue welfare certifications and implement responsible care standards that prioritize animal well-being over profit margins. Some operators have completely transformed their business models, shifting from exploitation to conservation education.

Ethical Alternatives That Benefit Everyone

Modern elephant tourism offers several humane alternatives that create meaningful experiences without compromising animal welfare:

- Volunteer-based programs that allow visitors to assist with elephant care tasks like preparing food and maintaining enclosures

- Guided educational visits that focus on elephant biology, conservation challenges, and natural behaviors

- Photography tours that capture elephants in their natural habitat without direct interaction

- Sanctuary visits where elephants roam freely and visitors maintain respectful distances

- Conservation workshops that teach about elephant intelligence and social structures

These alternatives provide tourists with authentic experiences while supporting elephant welfare. Visitors often report deeper satisfaction from observing natural behaviors rather than forced performances. The educational component helps travelers understand why traditional riding practices cause harm, creating advocates who spread awareness when they return home.

An increasing number of travelers actively seek out ethical elephant experiences. Cultural awareness campaigns have helped shift public perception, making responsible tourism choices more mainstream. Wildlife advocates use social media and travel platforms to promote sanctuaries that prioritize animal welfare over entertainment value.

Tourism operators who embrace these changes often discover improved long-term sustainability. Ethical practices attract conscientious travelers willing to pay premium prices for authentic experiences. These businesses build stronger reputations and avoid potential backlash from animal rights campaigns.

The transformation hasn’t happened overnight, but momentum continues building across Southeast Asia and other elephant tourism destinations. Countries like Thailand have seen significant policy changes, with some provinces implementing stricter regulations on elephant interactions. Tourism boards increasingly promote observation-based experiences in their marketing materials.

Sanctuary programs that focus on rehabilitation and natural behavior enhancement have proven particularly successful. These facilities provide elephants with environments that support their physical and psychological needs. Visitors witness the dramatic difference between elephants in sanctuary settings versus those used for riding, creating powerful learning experiences.

Educational components have become central to ethical elephant tourism. Guides explain elephant anatomy, social structures, and conservation challenges during visits. Technological advances have enabled virtual reality experiences that simulate close elephant encounters without physical contact.

The shift represents more than changing tourist activities – it reflects a broader evolution in how humans relate to wildlife. Travelers increasingly value authentic animal behavior over staged performances. This transformation benefits not only elephants but also local communities that develop sustainable tourism models based on conservation rather than exploitation.

Professional veterinarians and animal behaviorists strongly support these alternative approaches. Their research demonstrates how observation-based tourism reduces stress levels in elephant populations while maintaining economic benefits for local communities. The evidence continues mounting that ethical elephant tourism creates win-win scenarios for animals, tourists, and operators willing to adapt their practices.

Why Natural Evolution Never Prepared Elephants for Carrying Riders

I’ve studied countless elephant anatomy diagrams and observed these magnificent creatures in their natural habitats, and one thing becomes crystal clear: evolution designed elephants to be walking monuments, not living pack animals. Their skeletal architecture tells a fascinating story of millions of years of adaptation that never included human passengers.

Pillar-Like Legs Support Vertical Weight Distribution

Elephants developed four incredibly strong, column-like legs that function as living pillars, distributing their massive body weight—which can reach up to 14,000 pounds—evenly downward through their bones. I notice how their leg bones align almost perfectly vertical, creating a straight load path from their body mass directly to the ground. This ingenious design allows them to stand motionless for hours without strain, but it doesn’t account for additional weight pressing down on their spinal column.

Their spine naturally curves in a way that supports their enormous internal organs and body mass hanging beneath it, much like a bridge suspension system. However, when riders sit on top, this careful balance gets disrupted. The additional weight creates unnatural pressure points along their vertebrae, forcing their spine to bear loads it simply wasn’t built to handle.

Anatomical Differences from True Pack Animals

I find it striking how horses and donkeys evolved completely different spinal structures specifically suited for carrying loads. These animals developed stronger, more flexible backs with better shock absorption capabilities. Their skeletal systems can distribute rider weight effectively across multiple vertebrae and supporting muscles.

Elephants lack these critical adaptations. Consider how their shoulder blades sit differently than horses—they’re positioned in a way that creates pressure points when carrying gear or riders. Their spinal processes (the bony projections along their backs) are shaped for supporting hanging weight from below, not for bearing additional loads from above.

The consequences become even more concerning when I think about duration. While nature’s most dangerous predators might inflict quick damage, the chronic pain from repeated riding sessions builds silently over months and years. Elephants can’t vocalize their discomfort the way other animals might, making their suffering largely invisible to untrained observers.

Their massive size actually works against them in this context. What seems like a minor addition—a human rider weighing 150 pounds—becomes significant when multiplied across hours of walking on uneven terrain. Unlike the quick movements of animals built for speed, elephants must bear this extra load through their slow, deliberate steps, amplifying the stress on their unprepared spinal structure.

Sources:

bioengineering.hyperbook.mcgill.ca

PMC (2021) – Kongsawasdi et al.

asianelephantsupport.org

Elephantstay