Nearly 64% of U.S. adults have experienced at least one Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE), with family trauma creating biological changes that persist across decades and significantly increase risks for chronic diseases, mental health disorders, and cognitive decline.

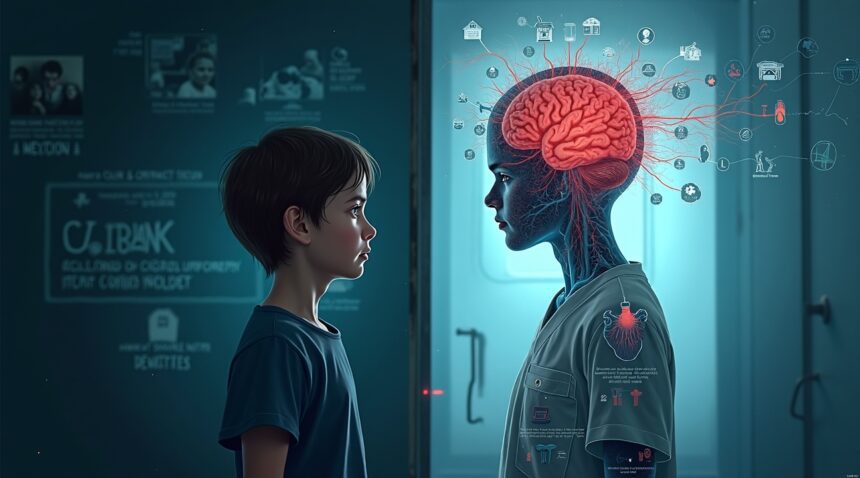

Toxic stress resulting from childhood family trauma has profound and long-lasting effects on both the brain and body. During critical periods of development, this stress rewires neurological pathways, sparks chronic inflammation, and disrupts the normal release of stress hormones such as cortisol. These biological changes can manifest later in life as a wide range of serious physical and mental health conditions, contributing to lifelong struggles for trauma survivors.

Key Takeaways

- Adults with four or more ACEs face significantly higher rates of heart disease, diabetes, cancer, and early death. They also report 40% greater mobility impairments and 80% more difficulty with everyday tasks in later years.

- Childhood family trauma increases mental health risks, including depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and substance use disorders. These individuals are also 40% more likely to experience cognitive decline as they age.

- Trauma is linked to generational poverty and disadvantage. Women, in particular, face elevated risks of early childbirth and long-term health problems, highlighting the gendered impact of ACEs.

- The biological toll of toxic stress is long-term, leading to chronic inflammation, disrupted cortisol rhythms, and even changes in brain structure that persist well into adulthood.

- Solutions exist to break trauma cycles, including early intervention programs, trauma-informed healthcare practices, and policies that promote economic stability and supportive family environments.

Learn More About ACEs and Their Impacts

To dive deeper into the science behind Adverse Childhood Experiences, their lifelong effects, and prevention strategies, visit the CDC’s ACEs information page.

Nearly 64% of U.S. Adults Have Experienced Childhood Trauma – And the Numbers Keep Climbing

The statistics surrounding childhood trauma paint a sobering picture of American families. I’ve examined recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which reveals that nearly 64% of U.S. adults have experienced at least one Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE). Even more alarming, one in six adults reports having endured four or more traumatic experiences during their formative years.

These numbers represent millions of individuals carrying invisible wounds from their childhood. Close to half of all children in the United States face exposure to traumatic social or family incidents while their brains are still developing. Such widespread prevalence means that childhood trauma affects not just individual families but entire communities and generations.

The CDC categorizes ACEs into three primary areas that encompass the most damaging experiences children can face. Abuse includes physical, emotional, and sexual maltreatment that directly harms a child’s sense of safety and self-worth. Neglect involves the failure to meet basic physical and emotional needs, creating profound feelings of abandonment. Household dysfunction represents the third category, covering situations where children witness or experience unstable family environments.

The Most Common Forms of Childhood Trauma

Domestic violence stands as one of the most prevalent forms of household dysfunction affecting children today. When children witness violence between caregivers, they experience chronic stress that reshapes their developing nervous systems. Parental substance abuse represents another significant category, creating unpredictable and often dangerous home environments where children can’t rely on consistent care or protection.

Additional household dysfunction factors include:

- Mental illness in family members that goes untreated

- Incarceration of a household member

- Parental separation or divorce handled in harmful ways

- Emotional unavailability of primary caregivers

The cumulative effect of multiple ACEs creates what researchers call a “dose-response relationship.” This means that each additional traumatic experience exponentially increases the likelihood of developing serious health problems later in life. Adults with four or more ACEs show dramatically higher rates of depression, anxiety, substance abuse, and chronic diseases like heart disease and diabetes.

I’ve observed that many people don’t recognize their childhood experiences as traumatic, particularly when they involve emotional neglect or chronic stress rather than obvious abuse. This lack of awareness can prevent individuals from seeking appropriate help or understanding why they struggle with certain health issues in adulthood. The body keeps score of these early experiences, even when the conscious mind has adapted to survive.

Recent research suggests these numbers may actually underestimate the true scope of childhood trauma. Many ACEs studies focus on household-based trauma while overlooking community violence, bullying, medical trauma, or systemic issues like poverty and discrimination. Additionally, cultural factors may influence how willing people are to disclose traumatic experiences in survey settings.

The climbing statistics reflect both increased awareness and reporting of childhood trauma, as well as genuine increases in family stress factors. Economic pressures, social isolation, and mental health challenges in parents contribute to environments where children face higher risks of traumatic experiences. Social media and technology have also introduced new forms of trauma exposure that previous generations didn’t face.

Understanding these prevalence rates helps explain why so many adults struggle with seemingly unexplained physical symptoms, relationship difficulties, or mental health challenges. The connection between childhood experiences and adult health outcomes has become impossible to ignore, particularly as research continues to demonstrate the biological mechanisms through which early trauma affects lifelong wellbeing.

These statistics also highlight the critical importance of early intervention and prevention programs. When nearly two-thirds of adults carry trauma from childhood, addressing these issues becomes a public health imperative rather than an individual clinical concern. Recognizing the widespread nature of childhood trauma helps reduce stigma and encourages more people to seek healing.

Individuals with Four or More ACEs Face Dramatically Higher Chronic Disease Risks Throughout Life

When children experience four or more adverse childhood experiences, I observe that their bodies carry these wounds well into adulthood through dramatically elevated chronic disease risks. Research reveals striking differences between individuals who experienced minimal childhood trauma and those who endured multiple adverse events.

Major Chronic Disease Patterns

People with four or more ACEs develop heart disease, stroke, diabetes, cancer, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at rates that far exceed those with protective childhoods. Beyond these conditions, affected individuals also face increased injury rates, sexually transmitted infections, and teen pregnancies. Most concerning, early death becomes a genuine threat for this population.

The CDC’s ACE Study, which followed over 17,000 participants, demonstrates how toxic stress from multiple childhood traumas disrupts critical bodily systems. The brain, immune, and endocrine systems bear the heaviest burden from this early damage. These disruptions create cascading health problems that persist for decades.

Physical Disability and Daily Function Impacts

Adults who experienced multiple childhood traumas show impaired immune and stress-response systems that translate into measurable physical limitations. Statistics reveal these individuals are 40% more likely to experience mobility impairments during their later years. Even more striking, they’re 80% more likely to struggle with everyday tasks as they age.

The contrast between health outcomes becomes stark when comparing different ACE scores. Those with zero adverse experiences maintain significantly better physical function, while individuals reporting four or more ACEs face compounding challenges. Their bodies simply can’t recover from the chronic inflammation and stress hormone disruption that began in childhood.

Toxic stress essentially rewires developing bodies in ways that promote disease formation. Elevated cortisol levels damage cardiovascular systems, while chronic inflammation creates conditions ripe for cancer development. Diabetes risk increases as stress hormones interfere with normal glucose regulation. These aren’t isolated health events but interconnected consequences of early trauma exposure.

Physical disability often emerges gradually for trauma survivors. Joint problems, chronic pain, and reduced stamina become common complaints that limit daily activities. Simple tasks like climbing stairs or carrying groceries become increasingly difficult. Emotional processing challenges compound these physical limitations, creating cycles where mental and physical health problems reinforce each other.

The research consistently shows that childhood trauma literally gets under the skin, altering biological processes in ways that promote chronic disease throughout the lifespan. Understanding these connections helps explain why some adults struggle with multiple health conditions while others maintain vitality well into their golden years.

Family Trauma Triggers Mental Health Disorders and Cognitive Decline Decades Later

Childhood family trauma creates lasting ripple effects that extend far beyond the initial traumatic experience. When someone grows up in an environment marked by abuse, neglect, or severe dysfunction, their brain develops under chronic stress conditions that fundamentally alter its structure and function. These changes don’t simply fade with time – they persist across decades, manifesting as serious mental health conditions and cognitive problems well into adulthood and old age.

Adults who experienced family trauma during their formative years face a dramatically increased risk of developing depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and substance use disorders. The connection isn’t coincidental – trauma literally rewires the developing brain in ways that make these conditions more likely. Stress hormones flood young neural pathways, disrupting normal development patterns and creating vulnerabilities that surface years or even decades later.

The relationship between childhood family trauma and mental illness follows a clear dose-response pattern. Higher scores on the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) assessment correlate directly with increased rates of serious mental health problems throughout life. Someone with multiple traumatic experiences doesn’t just face slightly higher risks – they encounter sharply elevated probabilities of persistent behavioral health concerns that can dominate their adult experience.

Cognitive Function Suffers Long-Term Damage

Perhaps most troubling is the emerging evidence about family trauma’s impact on cognitive abilities later in life. Adults who come from traumatic or deeply unhappy family environments are 40% more likely to develop mild cognitive impairment in old age. This statistic reveals how early trauma creates vulnerabilities that don’t manifest until the brain begins its natural aging process.

The mechanisms behind this cognitive decline are complex but well-documented. Chronic stress during childhood disrupts the formation of secure attachment patterns, which are fundamental to healthy brain development. When a child’s primary relationships are sources of fear rather than safety, their developing brain prioritizes survival responses over learning and memory consolidation.

Key areas affected by early family trauma include:

- Memory formation and retrieval systems

- Executive brain function, including planning and decision-making abilities

- Learning capacity and information processing speed

- Emotional regulation and stress response mechanisms

- Attention and concentration capabilities

These deficits compound over time because trauma-affected brains remain in a heightened state of alertness that’s exhausting to maintain. The constant vigilance required to navigate unpredictable family environments drains cognitive resources that should be devoted to learning and development. Stress responses that were once adaptive become maladaptive when they persist into safe environments.

Memory and learning capabilities suffer particularly severe impacts because trauma disrupts the hippocampus, a brain region critical for forming new memories and retrieving existing ones. Children from traumatic families often struggle academically not because they lack intelligence, but because their brains are preoccupied with monitoring for threats rather than absorbing information.

Executive brain function – the mental skills that include working memory, flexible thinking, and self-control – also shows lasting impairment. These skills are essential for success in work, relationships, and daily life management. When family trauma damages these capabilities early in life, the effects cascade through every subsequent life stage.

The enduring nature of these impacts stems from how trauma affects brain architecture during critical developmental periods. Unlike physical injuries that heal, neurological changes from chronic childhood stress become embedded in the brain’s structure. This explains why someone might develop cognitive problems decades after their traumatic experiences ended, as the brain’s compensatory mechanisms finally begin to fail under the cumulative stress of a lifetime.

Understanding these long-term consequences helps explain why family trauma recovery requires more than simply removing someone from a dangerous situation. The neurological changes demand active intervention and often lifelong management strategies to prevent or minimize the emergence of mental health disorders and cognitive decline in later decades.

Childhood Trauma Creates Cycles of Poverty and Disadvantage That Span Generations

Family trauma doesn’t just affect the immediate victim – it ripples through generations, creating persistent patterns of disadvantage that can be difficult to break. When children experience toxic stress and trauma within their families, I observe how these experiences fundamentally alter their developmental trajectory, setting them up for challenges that often persist well into adulthood.

Educational and Economic Consequences

Children who endure family trauma frequently struggle with academic achievement, which directly impacts their future earning potential. These students often have difficulty concentrating, forming relationships with teachers, and maintaining consistent attendance. As adults, trauma survivors typically face unstable employment patterns and experience higher rates of financial insecurity compared to their peers who didn’t experience early adversity.

The economic impact extends far beyond individual circumstances. When trauma survivors become parents themselves, their children inherit not only genetic predispositions but also environmental stresses that perpetuate cycles of disadvantage. Limited financial resources restrict access to quality education, healthcare, and stable housing — all factors that contribute to continued intergenerational trauma.

Health Disparities and Women’s Unique Vulnerabilities

Women who experienced childhood trauma face particularly complex challenges that affect both their immediate circumstances and long-term health outcomes. Research shows these women are significantly more likely to experience early or non-marital childbirth, which often compounds existing socioeconomic pressures. The combination of young motherhood and limited resources creates additional stress that can affect both mother and child.

The health consequences for women continue throughout their lives, with trauma survivors showing elevated rates of chronic conditions including cancer and diabetes. These conditions often develop earlier and progress more aggressively than in women without trauma histories. Lower-income and marginalized communities experience disproportionately higher rates of these health complications, creating a perfect storm of medical and financial burden.

Healthcare access becomes particularly challenging for trauma survivors, who may distrust medical professionals or avoid seeking care due to past negative experiences. This avoidance can delay critical interventions and allow conditions to worsen, ultimately requiring more expensive emergency treatments that further strain already limited resources.

Financial instability intersects with health challenges in ways that compound both problems:

- Medical debt can push families deeper into poverty.

- Lack of resources prevents access to preventive care.

- Children witness and internalize patterns of trauma-induced instability.

Breaking these cycles requires understanding how deeply interconnected trauma, health, and socioeconomic status really are, particularly for women and marginalized communities who face the greatest barriers to recovery and stability.

Stable Support and Early Intervention Can Break the Trauma Cycle

Creating safe, nurturing environments for children can dramatically reduce the devastating effects of childhood trauma on lifelong health. I’ve observed that consistent caregiving acts as a powerful buffer against toxic stress, fundamentally altering developmental trajectories and preventing the accumulation of health risks that often emerge in adulthood.

Early intervention programs deliver the most significant protective benefits because they address trauma-related outcomes before these issues become entrenched patterns. When families access support during critical developmental windows, children develop stronger resilience mechanisms that serve them throughout their lives. Understanding emotional development becomes crucial during these formative years.

Proven Strategies for Breaking Trauma Cycles

Several evidence-based approaches have demonstrated measurable success in preventing trauma’s long-term impact:

- ACEs screening programs that identify at-risk children and connect families with appropriate resources

- Trauma-informed care protocols that recognize signs of distress and respond with understanding rather than punishment

- Enhanced family and social support networks that provide stability during crisis periods

- Trauma-sensitive education practices that create safe learning environments for affected children

- Expanded access to mental health services that address both immediate needs and long-term healing

Economic policy interventions play an equally important role in trauma prevention. Living wage policies reduce family stress by providing financial stability, while paid family leave allows parents to maintain strong bonds with their children during critical periods. Philanthropic efforts often supplement these policy measures by funding community-based programs.

Research consistently shows that children who receive stable support during their early years develop stronger coping mechanisms and experience fewer physical health problems later in life. Trauma-informed care approaches recognize that behavioral issues often stem from underlying trauma rather than defiance, leading to more effective interventions.

I’ve found that comprehensive prevention strategies work best when they address multiple risk factors simultaneously. Recognition of achievement in trauma-informed programs encourages continued investment in these vital interventions. Communities that implement coordinated support systems see significant improvements in child welfare outcomes and reduced healthcare costs over time.

The effectiveness of early intervention cannot be overstated – every dollar invested in prevention programs saves communities substantially more in future healthcare, criminal justice, and social service costs. Building resilience through stable relationships and responsive care creates positive cycles that benefit not only individual children but entire communities for generations.

How Toxic Stress Rewires the Body and Brain for a Lifetime of Health Problems

Childhood trauma doesn’t simply fade away as children grow older—it embeds itself into the very biology of their developing bodies and brains. When children experience multiple adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), their stress-response systems shift into overdrive, creating lasting changes that persist well into adulthood. These biological alterations form the foundation for a wide range of health problems that can emerge decades later.

The body’s stress-response system, designed to handle short-term threats, becomes chronically activated in children facing ongoing trauma. Stress hormones like cortisol flood the developing system at levels far beyond what nature intended. Instead of the normal peaks and valleys of cortisol production, traumatized children often maintain persistently elevated levels that disrupt normal development processes. This constant state of biological alarm interferes with critical developmental windows when the brain, immune system, and metabolic functions are taking shape.

The Biological Cascade of Trauma

Scientific research reveals striking differences between trauma survivors and those without ACE exposure across multiple biological markers. Brain imaging studies show structural changes in regions responsible for memory, emotional regulation, and decision-making. Children who experience trauma develop differences in brain architecture that can affect learning, relationship formation, and stress management throughout their lives.

The immune system bears a particularly heavy burden from toxic stress. Chronic inflammation becomes a hallmark of trauma exposure, with elevated inflammatory markers appearing in blood tests years after the original traumatic events. This persistent inflammation creates a biological environment that accelerates aging processes and increases vulnerability to autoimmune disorders. The body essentially remains in a state of heightened alert, treating normal life stressors as existential threats.

Metabolic disruption represents another critical pathway through which childhood trauma influences lifelong health. Stress hormones interfere with normal insulin function and glucose regulation, setting the stage for diabetes and cardiovascular disease decades later. The body’s energy systems become dysregulated, affecting everything from appetite control to fat storage patterns. These changes help explain why trauma survivors face elevated risks for obesity, heart disease, and metabolic disorders even when controlling for lifestyle factors.

Cortisol rhythms, which normally follow predictable daily patterns, become disrupted in trauma survivors. Healthy individuals experience cortisol peaks in the morning that gradually decline throughout the day. However, those with ACE exposure often show flattened or irregular patterns that persist into adulthood. This disrupted rhythm affects sleep quality, immune function, and the body’s ability to recover from daily stressors.

The brain’s stress-processing centers undergo particularly profound changes during traumatic exposure. Areas like the amygdala, responsible for threat detection, become hyperactive and enlarged. Meanwhile, the prefrontal cortex, which manages rational thinking and emotional regulation, may develop differently or remain underactive. These structural changes create a brain that’s primed to perceive danger even in safe environments, leading to heightened anxiety, difficulty with relationships, and challenges in academic or work performance.

Research demonstrates that these biological changes don’t occur uniformly across all trauma types or individuals. The timing, duration, and severity of traumatic experiences influence the extent of biological disruption. Early trauma appears particularly damaging because it occurs during critical developmental periods when biological systems are establishing their baseline functioning patterns.

Inflammation markers serve as particularly reliable indicators of trauma exposure. Studies consistently show elevated levels of inflammatory proteins like C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 in adults who experienced childhood trauma. This chronic inflammatory state contributes to premature aging and increased disease risk, creating a biological environment that ages the body faster than normal.

The persistence of these biological changes underscores why trauma’s effects extend far beyond psychological symptoms. Even when individuals develop effective coping strategies or receive therapeutic intervention, some biological signatures of early trauma exposure may remain detectable. Understanding these mechanisms helps explain why trauma survivors face elevated risks for seemingly unrelated health conditions and why comprehensive treatment approaches must address both psychological and physical health needs.

Sources:

The National Child Traumatic Stress Network

“Unhappy Family or Trauma in Youth Leads to Poor Health in Old Age,” UCSF

“How childhood trauma can affect health for a lifetime,” Penn State Health

“Childhood Trauma Has Lifelong Health Consequences for Women,” Population Reference Bureau

About Adverse Childhood Experiences – CDC

“How Childhood Trauma May Impact Adults,” University of Rochester Medical Center Newsroom

“Nearly Half of U.S. Kids Exposed To Traumatic Social or Family Experiences During Childhood,” Johns Hopkins University Public Health

“Adult survivors of childhood trauma: Complex trauma, complex needs,” Australian Journal of General Practice